- Date

What Happened to Do Not Track DNT and Is It Still Relevant

Andrii Romasiun

Andrii Romasiun

What Was Do Not Track and What Did It Promise?

The Do Not Track (DNT) standard started with a simple, powerful idea: a universal "off switch" for online tracking.

Think of it like putting a ‘no junk mail’ sign on your physical mailbox. That was the elegant concept behind Do Not Track, a privacy feature that let people signal their desire to opt out of being followed around the web. It grew out of a rising discomfort with how websites and advertisers were shadowing users' every move online.

The real beauty of DNT was its promised simplicity. Instead of navigating a maze of cookie settings on every single site, you could just flip one switch in your browser. That single setting would then send an automated, unambiguous message to every website you visited: "Please do not track my activity."

A Promise of Universal Privacy

At its heart, the goal was to establish a universal, user-controlled standard for online privacy. It was meant to shift the balance of power back to the individual, giving them a way to state their privacy preference once and have it respected everywhere. This idea created a lot of buzz among privacy advocates and everyday users who felt helpless against murky data collection.

The Do Not Track initiative had a few key aims:

- Simplifying Privacy Choices: Offer one straightforward setting to control tracking across the board.

- Creating a Standard Signal: Develop a consistent technical signal that all websites could easily interpret.

- Empowering Users: Give people a direct say in how their browsing data was used, especially for targeted advertising.

But the road from a great idea to a working reality was full of potholes. The initiative got some early momentum, even earning a nod from the US Federal Trade Commission back in 2010. Unfortunately, it ultimately fell apart after nearly a decade, mainly because it was never widely adopted and, crucially, had no enforcement behind it.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) officially pulled the plug on its Tracking Protection Working Group in January 2019, stating that "insufficient deployment" was the final nail in the coffin. You can read more about this decision and how it shaped the conversation around privacy signals.

The core failure of DNT wasn't technical; it was political. The signal was a polite request, not a legal demand, and the advertising industry largely chose to ignore it.

To really grasp its journey, it helps to see what DNT was supposed to be versus what it actually became.

Do Not Track Intention vs Reality

The table below breaks down the gap between the dream of DNT and its disappointing reality. It highlights how a well-intentioned privacy tool failed to gain the traction it needed to be effective.

| Aspect | Intended Purpose (The Dream) | Actual Outcome (The Reality) |

|---|---|---|

| User Control | A powerful, universal opt-out for all tracking. | A polite request that most websites and ad networks ignored. |

| Industry Adoption | Widespread, voluntary compliance driven by respect for users. | Inconsistent adoption; many major players refused to honor it. |

| Legal Standing | A recognized standard that could inform future privacy laws. | No legal or regulatory teeth, rendering it effectively unenforceable. |

| Effectiveness | Users could browse freely without being monitored for ad targeting. | Minimal impact on tracking; users were still profiled extensively. |

Ultimately, DNT serves as a classic example of a good idea that couldn't overcome industry resistance and the lack of a legal mandate. It was a voluntary system in a world that needed rules.

How the DNT Signal Actually Worked

![]()

To really get why the Do Not Track standard never quite took off, you have to understand just how simple it was from a technical standpoint. There was no complex software or fancy verification system. The whole thing was built on a single, tiny piece of information your browser sent to the websites you visited.

This piece of info is called an HTTP header. Think of it like a little note attached to every request your browser makes. When you click a link, your browser asks the server for the page, and the DNT header was just one line in that request, quietly stating your privacy preference.

The idea was beautifully simple. If you turned on DNT in your browser, it would automatically stick this header onto all of your web traffic. It was an elegant, lightweight way to communicate "please don't track me" to every site on the internet.

The Three DNT Signal Values

The Do Not Track header wasn't a blunt on/off switch. It actually had three distinct values to communicate your choice with a bit more nuance. This gave websites a clear signal about consent, refusal, or just plain neutrality.

Here’s what each value meant:

DNT: 1(Tracking is Not Allowed): This was the heart and soul of the DNT system. Sending a1meant you had explicitly opted out and did not want to be tracked. It was a clear and direct "no, thank you."DNT: 0(Tracking is Allowed): A value of0told the website you were perfectly fine with being tracked. This was less common, but it gave users a way to signal their approval for things like personalized ads or content.- Null (No Preference Set): If the header was missing altogether (a "null" value), it meant you hadn't expressed a preference either way. This was the default setting for most browsers, leaving the decision of whether to track up to the website.

This simple three-value system was designed to provide clear, machine-readable instructions. The

DNT: 1signal was the most important one, representing millions of users actively asking for more privacy.

The whole system was designed to work silently in the background. You’d flip a switch in your settings once, and your browser would handle the rest, sending the right signal with every single click.

Finding the DNT Setting in Browsers

Turning on this feature was incredibly easy, which was a big reason it gained traction among privacy-minded users. Most major browsers tucked a simple toggle switch into their privacy settings menus, making the "do not track dnt" option easy to find and enable.

For instance, here’s what the DNT setting looked like in an older version of Mozilla Firefox.

![]()

As you can see, users could just select "Always" to send the DNT signal everywhere they went online. This simple user experience was a huge plus, but as we'll see, a friendly interface couldn't make up for a complete lack of industry enforcement.

The technical elegance of the DNT header is a stark contrast to the messy political and business reasons it ultimately failed. The technology worked exactly as planned, but its fate was sealed by a total lack of agreement on what "honoring" the signal actually meant for businesses built on tracking data—a problem that still echoes in debates around modern cookie-less tracking methods.

Why the Do Not Track Standard Failed

The Do Not Track standard started with a bang. As privacy worries began to bubble up, major browsers like Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, and Microsoft Edge jumped on board, giving millions of people a simple, one-click switch to signal they didn't want to be tracked. It felt like a breakthrough—for the first time, users had an easy way to send a clear message to every website they landed on.

This first wave of adoption felt like a huge win for consumer privacy. The tech was simple, the user interface was clean, and the intent was unmistakable. But sending a signal is one thing; getting someone to listen is another story entirely. The real reason DNT failed wasn't a technical flaw, but a simple, collective decision by the industry to just ignore it.

The Problem of Voluntary Compliance

The fatal flaw of the Do Not Track DNT signal was that it was just a polite suggestion. It was designed as a request, not a legally binding command. There were no laws, no regulations, and certainly no penalties forcing websites and ad networks to respect the DNT: 1 header. This left the choice entirely up to the very companies whose business models often relied on collecting the data DNT was designed to protect.

So, what happened? The major advertising networks and tech giants decided to interpret the signal however they wanted, which usually meant ignoring it. They claimed there was no clear agreement on what "tracking" even meant. Does it count if you're just collecting analytics to improve your site? What about for security or fraud prevention? This convenient ambiguity became the perfect excuse to keep doing what they’d always done.

The DNT standard was like a global election where everyone could vote for privacy, but the results were non-binding. The industry simply chose not to certify the outcome.

This willful ignorance looks even worse when you see how many people actually used it. A 2019 study showed that 23% of people globally had enabled Do Not Track in their browsers. That’s a massive number of users—around 75 million Americans and 115 million EU citizens—all sending a DNT signal that was almost completely disregarded. A quarter of internet users made their preference clear, but without any legal teeth, their voices were lost in the noise. You can dig into more of the data in the full DNT Act of 2019 research.

Key Moments in DNT's Decline

A few key events hammered the final nails into DNT's coffin, signaling to everyone that the initiative had run out of steam.

The first major blow came from the very group trying to make it official. After years of heated arguments between privacy advocates and industry lobbyists, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) threw in the towel and shut down its Tracking Protection Working Group in January 2019. They just couldn't get everyone to agree, which made it crystal clear the industry was never going to voluntarily adopt a strong, enforceable standard.

Another nail was Apple’s decision to pull the DNT setting from Safari. Apple’s reasoning was that the signal had actually backfired. Since so few users enabled it, the presence of the DNT: 1 header became a unique identifier—a "fingerprint"—that could ironically make it easier to track the very people trying to protect their privacy.

Instead, Apple rolled out its own aggressive, on-by-default feature called Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP). ITP doesn't just ask trackers to stop; it actively blocks them. This move showed a major shift in strategy: why ask nicely when you can just build a technical wall? These actions pretty much cemented DNT's status as a failed experiment, a relic from a time when we hoped for cooperation instead of regulation.

Global Privacy Control: The Successor DNT Was Meant To Be

With the Do Not Track standard now little more than a footnote in internet history, a smarter, more forceful signal has emerged. Think of Global Privacy Control (GPC) as the spiritual successor to DNT, built on the lessons learned from its predecessor's failure. It takes the same core idea but adds the one thing DNT never had: legal teeth.

On a technical level, GPC operates just like DNT. It's a simple signal sent from a browser or extension to tell websites about your privacy choices. The game-changing difference, however, is what happens when a website receives that signal. While DNT was a polite request that was mostly ignored, GPC is a legally binding instruction in many places.

From A Polite Request To A Legal Demand

The real power behind GPC comes from its direct connection to privacy laws like the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and its successor, the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). Under these laws, the GPC signal must be honored as a formal request from a user to opt out of the sale or sharing of their personal data.

This single change elevates a simple browser setting into a genuine consumer rights tool.

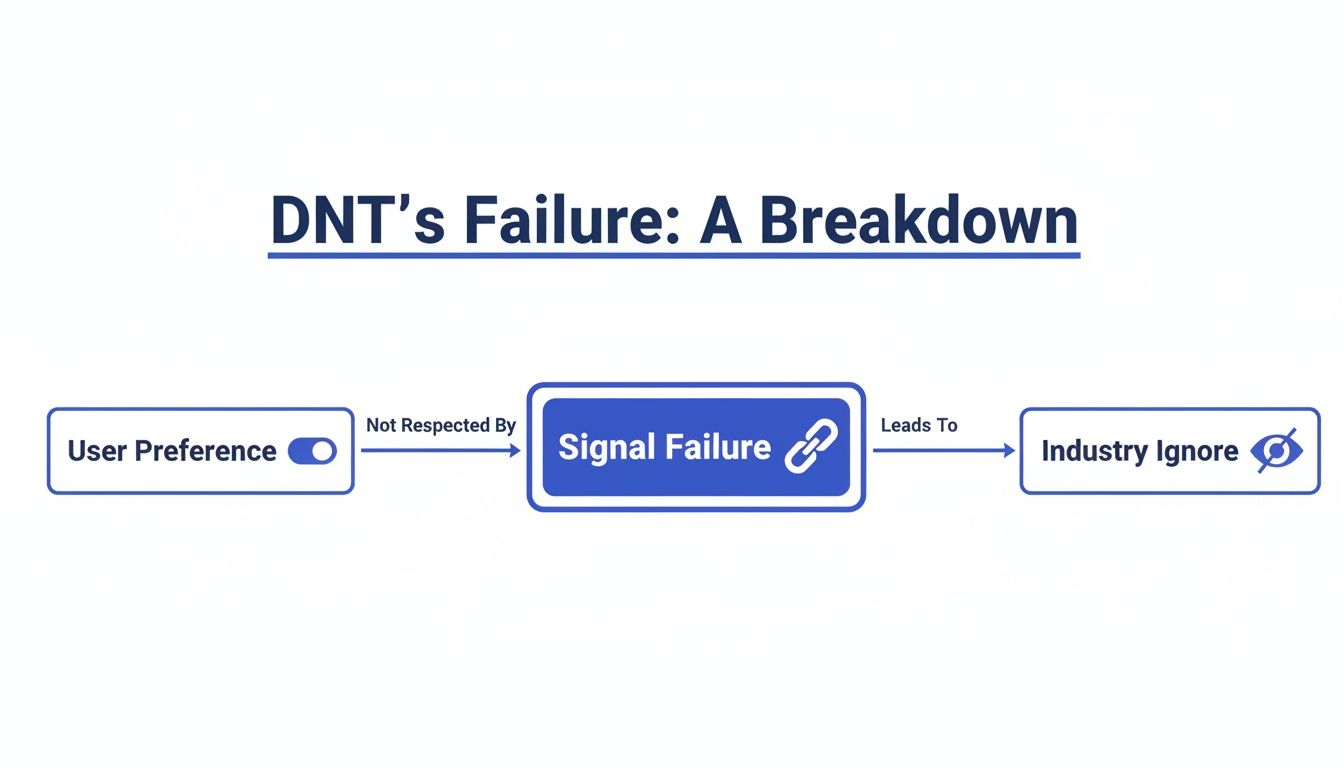

As the flowchart shows, DNT’s downfall was that a user’s preference was met with widespread industry indifference. GPC was designed specifically to fix this fatal flaw.

Other states, like Colorado, have followed suit, also recognizing GPC as a valid way for people to opt out. This growing legal foundation means businesses can no longer just ignore the signal; doing so means breaking the law. It’s a complete reversal from the voluntary, honor-system approach that doomed the original Do Not Track (DNT) initiative from the start.

You could say GPC is just DNT with a good lawyer. It turns a user's preference from a hopeful wish into an enforceable legal right, compelling companies to listen in a way they never did before.

Suddenly, there are real consequences—including hefty fines—for non-compliance. This is the enforcement mechanism that DNT was always missing.

How GPC Is Different From Do Not Track

While they might seem similar on the surface, the practical differences between GPC and DNT are night and day. Understanding them makes it clear why GPC is actually working.

Let’s quickly compare the two signals to see where GPC truly shines.

Comparing DNT and GPC Signals

| Feature | Do Not Track (DNT) | Global Privacy Control (GPC) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Backing | None. It was a voluntary standard with no legal weight. | Legally recognized under CCPA/CPRA, Colorado Privacy Act, and more. |

| Industry Adoption | Largely ignored. Most ad tech and publishers chose not to honor it. | Mandatory for businesses covered by relevant laws. Non-compliance carries legal risk. |

| Clarity of Purpose | Vague. What "tracking" meant was never clearly defined. | Specific. Tied directly to the legal definitions of "sale" and "sharing" of data. |

| User Intent | Ambiguous. Was it about ads, analytics, or all tracking? | Clear. Explicitly signals an opt-out of data sale/sharing. |

As you can see, GPC's strength comes from its legal foundation and clarity, forcing an industry-wide shift that DNT could only dream of.

This has major implications for website owners, especially when it comes to analytics. If you're serious about respecting user privacy, you need a system that properly handles GPC signals. This is why many are exploring privacy-first analytics tools. For those who want complete control over their data infrastructure, looking into self-hosted web analytics is a fantastic next step. It allows you to manage data on your own terms, ensuring you can fully align with your users' privacy choices.

How Website Owners Should Handle Privacy Signals

The privacy conversation usually focuses on what users can do, but let's flip the script. If you're a website owner, developer, or marketer, what happens on your end when a visitor lands on your site with a Do Not Track (DNT) or Global Privacy Control (GPC) signal switched on?

That's the million-dollar question. While the original do not track dnt signal isn't legally binding in most regions, your response says a lot about your brand. You could ignore it, sure. But choosing to respect it sends a clear, powerful message: you value user trust more than grabbing every last byte of data.

This isn't a decision without consequences, of course. When you honor a DNT request, you accept that some data points for your funnel analysis or audience segments will be missing. But it's a trade-off that often pays for itself in the long run.

Building a loyal user base is all about trust. And there are few better ways to earn it than by voluntarily respecting a user's explicit privacy choices.

This isn't just some fringe issue, either. A meaningful slice of your audience is actively sending these signals. Data from Baycloud.com's EU systems reveals that about 15% of users send a DNT signal. Mozilla's own telemetry backs this up, showing similar figures in the US (12.9%) and across major European countries. You can dig into even more data over at Quantable.com.

Implementing a Respectful Approach

Putting this into practice is more straightforward than it sounds. The basic idea is simple: check for the DNT or GPC header in a visitor's request before you fire up any tracking scripts.

Here’s what that logic looks like in simplified pseudocode for a DNT header:

// Check for the DNT header value from the browser

const dntHeader = navigator.doNotTrack;

// The DNT signal is '1' if the user has opted out

if (dntHeader !== '1') {

// DNT is off or not specified, so we can load analytics

loadAnalyticsScript();

} else {

// DNT is on, so we respect the user's choice

console.log("Do Not Track signal detected. Analytics script not loaded.");

}

This simple if/else statement ensures your analytics or ad scripts only run for visitors who haven't opted out. You can use a similar check for the GPC header (navigator.globalPrivacyControl).

Balancing Data Needs with User Privacy

Respecting DNT and GPC doesn't mean you have to operate in the dark. It just means you need to shift your mindset—and your tools. Privacy-first analytics platforms are built for this very purpose, giving you valuable insights without collecting personal data.

When you take this path, you're not just doing the right thing; you're aligning your business with a powerful consumer movement demanding digital respect. It also helps future-proof your site against new privacy laws that are constantly emerging. Getting a handle on regulations is critical, and our guide to GDPR compliance for websites is a great place to start.

Ultimately, respecting these signals is a strategic move that builds brand integrity and earns the kind of user loyalty that data alone can't buy.

The Lasting Legacy of Do Not Track

It’s tempting to write off Do Not Track (DNT) as a failure, but that's a bit too simple. The technology itself worked just fine—browsers sent the signal as designed. The real breakdown happened with the social contract, or lack thereof, on the receiving end.

Still, DNT's true legacy isn't its technical outcome. It's the worldwide conversation it started about online privacy and what user consent should actually mean.

Before DNT, the idea of a universal, browser-based privacy signal was pretty much an academic discussion. DNT pushed it into the mainstream, giving millions of people their first real tool to say, "Hey, I'd rather you didn't track me." Even though most websites ignored it, the signal was sent, and a seed was planted. It made people aware that their clicks and scrolls were being watched, and maybe, just maybe, they should have some control over it.

This shift in public awareness was a huge first step. It created the kind of grassroots and political pressure that paved the way for the legally enforceable privacy rules we have today.

From a Spark to a Fire

You can think of DNT as the spark that eventually ignited modern privacy regulations. It clearly showed that a voluntary, "honor system" approach to privacy was never going to work. When regulators needed proof that companies wouldn't respect user privacy without a legal reason to, the widespread disregard for DNT became Exhibit A.

This collective shrug from the industry was a powerful argument for creating laws with actual teeth, like Europe's GDPR and California's CCPA.

Without the hard lessons from DNT’s flop, it’s a safe bet we wouldn't have seen more effective solutions like Global Privacy Control (GPC) emerge so quickly. DNT walked so GPC could run. It proved the concept of a browser signal was sound, but it also proved that without legal backing, it was just noise.

Do Not Track was less of a technical standard and more of a global petition for privacy. Though the petition was denied, the signatures were seen, and the message was heard, paving the way for legally binding action.

The Rise of a Privacy-First Mindset

The core idea behind DNT is far from dead. It lives on in the new privacy laws, but also in a new wave of technologies built with privacy as a foundational principle, not an afterthought.

The growth of privacy-first analytics tools—like what we're building here at Swetrix—is a direct result of the principles DNT first brought to light. These platforms are designed from the ground up to deliver useful insights without having to harvest personal data.

This new way of thinking fulfills the original promise of DNT: building a web that's more transparent, respectful, and puts people back in control. So, instead of a failure, DNT is better understood as a crucial catalyst. It was a bold and necessary experiment that, even in its own downfall, managed to change the course of online privacy for the better.

Your Questions About DNT, Answered

Even though Do Not Track (DNT) is mostly a relic of a different era of the web, it still sparks a lot of questions. Let's clear up some of the most common points of confusion about what it is, what it isn’t, and whether it still has a place in your browser settings.

Should I Still Bother Keeping Do Not Track Enabled?

Honestly, leaving DNT enabled in your browser won't hurt anything. Think of it as a quiet, passive protest—you’re signaling your preference for privacy, even if most sites aren't listening.

But for real privacy protection, you need to look elsewhere. DNT by itself is like a flimsy screen door against modern tracking techniques. Your best bet is to use browsers with robust, built-in tracking prevention like Firefox or Brave, install solid privacy extensions, and enable Global Privacy Control (GPC), which actually has legal teeth in places like California.

Is Do Not Track the Same Thing as Incognito Mode?

Not at all. They tackle completely different privacy problems, and it's a common mix-up.

- Do Not Track (DNT): This is a signal your browser sends out to websites, asking them not to follow you around the internet. It’s a request made to others.

- Incognito Mode: This is a local setting on your computer. It just tells your browser not to save your history, cookies, or form data from that session. It does absolutely nothing to hide your activity from the websites you visit, your internet provider, or your boss.

Incognito mode cleans up the evidence on your own machine. DNT was meant to ask others not to create that evidence in the first place.

Here's a simple way to think about it: Incognito Mode protects your data from other people who use your computer. DNT was designed to protect your data from the websites you visit.

Does DNT Block Ads?

Nope. DNT was never an ad blocker and was never intended to be one. Its only job was to ask advertisers not to build a profile on you to serve up hyper-targeted ads based on your browsing habits.

If you had DNT on, you’d still see just as many ads. The only difference is they were supposed to be generic, not creepy ones that followed you from site to site. To actually block ads, you need a dedicated ad-blocking extension or a browser that has one built-in.

So Why Did Apple Ditch DNT in Safari?

Apple dropped the DNT setting from Safari because, ironically, it ended up making users less private. Because so few people turned it on, the DNT: 1 signal became a weirdly unique identifier.

Trackers could use that signal as part of a "fingerprint"—a collection of your browser's unique settings—to identify and follow you more easily. Instead of just asking trackers to play nice, Apple built Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP), a powerful feature that actively blocks tracking scripts for all Safari users by default. It was a classic Apple move: stop asking for permission and start enforcing privacy directly.

Ready to understand your website visitors without compromising their privacy? Swetrix offers clear, actionable insights in a cookie-less, GDPR-compliant platform. Start your 14-day free trial today and see what privacy-first analytics can do for you.